Reconsidering Columbus Day with the Help of James Baldwin

A short excerpt from The Hidden Roots of White Supremacy

Dear #WhiteTooLong readers,

For those who are off work and school for tomorrow’s federal holiday—officially designated as Columbus Day but also sure to be also proclaimed by President Biden as Indigenous Peoples’ Day—I hope you’re enjoying the long weekend. I’m back home following a speaking engagement at Baylor University last week where I was in conversation with my friend and gifted author, Greg Garrett, about both of our new books.

Greg has a fantastic new book out—The Gospel According to James Baldwin. Here’s what I had to say about it in an official endorsement: “In this concise volume, Greg Garrett has given us an immense gift: a beautifully written and accessible window into the wisdom of James Baldwin. Garrett powerfully presents Baldwin as a compassionate witness, an unyielding prophet, and even a saint in the deepest meaning of that word. Garrett lets Baldwin’s incandescent writing shine through, illuminating a path forward and allowing us to see that we can do and be better than we are."

It looks like more than one reader has seen the connection between our books. Amazon’s algorithm currently has them paired (and both are currently discounted).

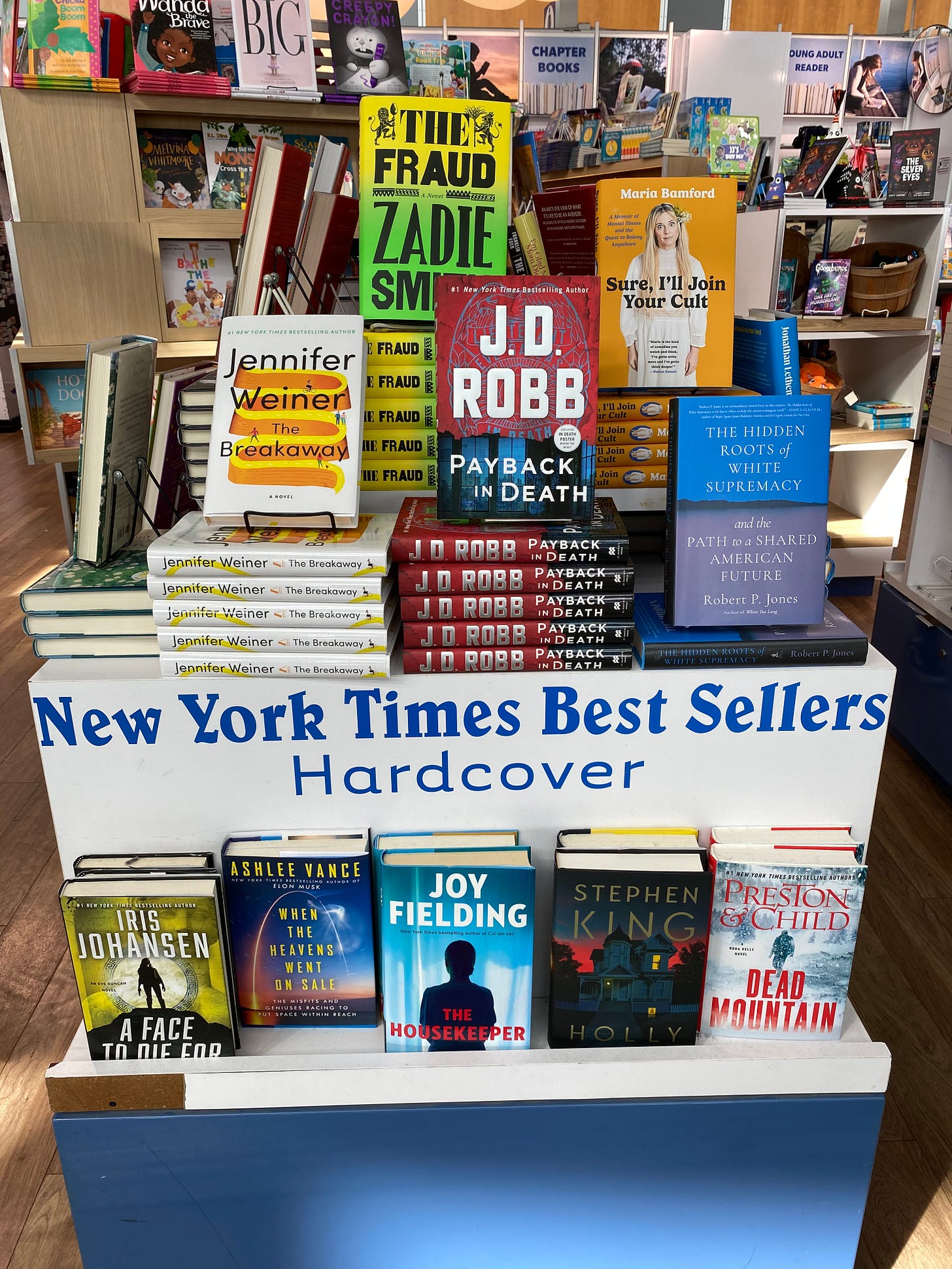

On my way home, I also had an author “bucket list” experience that stopped me in my tracks. At the Austin airport, I was pleasantly surprised to find my book on the “New York Times Best Sellers” display table at the front of the store.

This Sunday, I’m sharing a short excerpt from Hidden Roots in which I draw on the wisdom of James Baldwin to rethink our celebration of Columbus Day. Free subscribers will get the first part of the excerpt. Paid subscribers will get the entire excerpt, plus a voiceover of me reading it.

Warmly,

Robby

Reconsidering Columbus Day with the Help of James Baldwin

[NOTE: The following is an excerpt from my book, The Hidden Roots of White Supremacy and the Path to a Shared American Future, and is protected by copyright.]

Nearly six decades ago, in The Fire Next Time, James Baldwin vividly described the gift that a Black perspective holds for white Americans who are invested in a truer understanding of our shared history and our own heritage:

The American Negro has the great advantage of having never believed the collection of myths to which white Americans cling: that their ancestors were all freedom-loving heroes, that they were born in the greatest country the world has ever seen, or that Americans are invincible in battle and wise in peace, that Americans have always dealt honorably with Mexicans and Indians and all other neighbors or inferiors, that American men are the world’s most direct and virile, that American women are pure….

Negroes know far more about white Americans than that; it can almost be said, in fact, that they know about white Americans what parents—or, anyway, mothers—know about their children, and that they very often regard white Americans that way. And perhaps this attitude, held in spite of what they know and have endured, helps to explain why Negroes, on the whole, and until lately, have allowed themselves to feel so little hatred. The tendency has really been, insofar as this was possible, to dismiss white people as the slightly mad victims of their own brainwashing.1

One candidate for a more honest point of departure for America’s origin story is 1493—not the year Christopher Columbus “sailed the ocean blue,” but the year in which he returned to a hero’s welcome in Spain, bringing with him gold, brightly colored parrots, and nearly a dozen captive Indigenous people. It was also the year he was commissioned to return to the Americas with a much larger fleet of seventeen ships, nearly 1,500 men, and more than a dozen priests to speed the conversion of Indigenous people who inhabited what he, along with King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, still believed were Asian shores.

That trip resulted in the founding of La Isabela, in present-day Dominican Republic, the first permanent European occupation attempted in the Americas. While the colony would not last, the ripple effects of the journey would soon be felt in all spheres of human interaction and relationships….

The return of Columbus in 1493 also precipitated the culmination of one of the most fateful but unacknowledged theological developments in the history of the western Christian Church: the Doctrine of Discovery. Established in a series of fifteenth-century papal bulls (official edicts that carry the full weight of church and papal authority), the Doctrine claims that European civilization and western Christianity are superior to all other cultures, races, and religions.

From this premise, it follows that domination and colonial conquest were merely the means of improving, if not the temporal, then the eternal lot of Indigenous peoples. So conceived, no atrocities could possibly tilt the scales of justice against these immeasurable goods. With its fiction of previously “undiscovered” lands and peoples, the Doctrine fulfilled European rulers’ request for an unequivocal theological and moral justification for their new global political and economic exploits….

The Doctrine of Discovery, in short, merged the interests of European imperialism, including the African slave trade, with Christian missionary zeal….

The most relevant papal edict for the American context was the bull Inter Caetera, issued by Pope Alexander VI in May 1493 with the express purpose of validating Spain’s ownership rights of previously “undiscovered” lands in the Americas following the voyages of Columbus the year before. It praised Columbus, “who for a long time had intended to seek out and discover certain islands and mainlands remote and unknown and not hitherto discovered by others.” It again affirmed the church’s blessing of and interest in political conquest, “that in our times especially the Catholic faith and the Christian religion be exalted and be everywhere increased and spread, that the health of souls be cared for and that barbarous nations be overthrown and brought to the faith itself.”

As I’ve continued my reeducation journey over the last ten years, I have come to consider the Doctrine of Discovery as a kind of Rosetta Stone for understanding the deep structure of the European political and religious worldviews we have inherited in this country.

The Doctrine of Discovery furnished the foundational lie that America was “discovered” and enshrined the noble innocence of “pioneers” in the story we white Christian Americans have told about ourselves. It animated the religious and cultural worldview that delivered Europeans to these shores far before 1776 or 1619. Ideas such as Manifest Destiny, America as a city on a hill, or America as a new Zion all sprouted from the seed that was planted in 1493. This sense of divine entitlement, of European Christian chosenness, has shaped the worldview of most white Americans and thereby influenced key events, policies, and laws throughout American history….

If we go back to 1493, the protracted sweep of European contact with Native peoples is fully visible—as is the religious, cultural, and political worldview that motivated European conquest and colonization of “newly discovered” lands. This longer view also importantly reveals the connected historical streams of the US and the Americas, and of Native Americans, African Americans, and European Americans. Moreover, it brings us closer to the root of the problem: the disastrous cultural influence of the Christian Doctrine of Discovery, which continues to threaten the promise of a pluralistic American democracy.

Related on White Too Long

If you missed it last Thursday, I hope you’ll read my new essay arguing that it’s long past time to replace Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples’ Day.

Columbus Day Celebrates an Ongoing Threat to American Democracy

Dear #WhiteTooLong readers, Greetings from the Lone Star State! I’m having a long-anticipated conversation this afternoon (10/05) with my friend Greg Garrett at Baylor University. Greg has a fantastic new book out—The Gospel According to James Baldwin

And here are two other pieces from the archive that are related to today’s themes.

Gratitude for the Incandescent Witness of James Baldwin

Last Sunday, I had the honor of receiving a 2021 American Book Award, given by the Before Columbus Foundation for my recent book, White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity. I was floored to be in the company of such gifted authors, this year and across the rich legacy these awards have created for more than four decades. Pas…

My Fall Nonfiction Reading Recommendations

Dear #WhiteTooLong readers, Greetings from my week off, ahead of the home stretch leading to the publication of my new book, The Hidden Roots of White Supremacy and the Path to a Shared American Future, which will be published by Simon & Schuster on September 5th. This week also marks a milestone—I just received my author’s cache of advance books, allowi…